Let’s work together, be ambitious and say goodbye to American mink

A problem with invasive introduced species is that they leave you few choices: you suffer the damage, you control them, or you eradicate them. In most cases these are not exclusive, you might for example do some control but still suffer damage. Without eradication, the cost of damage and control remains year in, year out. This should lead inexorably to thinking in every case – ‘is eradication possible for this species?’. Not, is it difficult and challenging, which most significant eradication projects will be, but is it possible? Given the very significant damage that introduced species can cause, and the decidedly unattractive option of damage and control for ever, it is time to get ambitious with eradication.

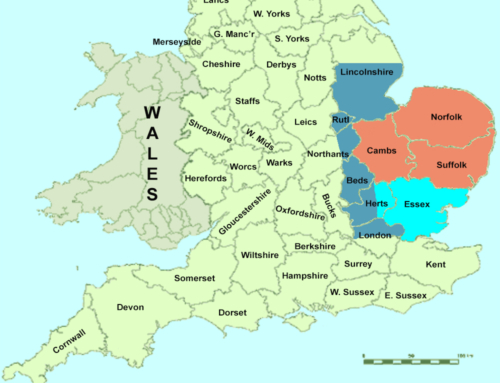

In East Anglia, significant ambition, backed by science might just be the beginning of the end for introduced American mink. Building on county-based control programmes, partners with an interest in reversing the huge decline in water voles (>90%) came together and set up Waterlife Recovery East. With the help of a Green Recovery Challenge Fund grant and support from partners such as Anglian Water, the IDBs and the Environment Agency, we set about removing mink from Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire. Within the project area we defined a Core where we could try to remove all the mink. Outside this, an intensely trapped Buffer, where we knew that there would always be immigration but we hoped that the 60km width of the Buffer, coupled with the topography, would be sufficient to stop immigration into the Core.

Extensive trapping using ‘smart traps’ started in January 2021. These are cage traps with a box of electronics on top (Remote Monitoring Device or RMD) that tell you by text and email immediately the trap door closes. In addition, it sends ‘heartbeat’ signals twice a day to the system to confirm that everything is working, only sending the volunteer trapper a message if there is a problem. The traps are placed in tunnels on rafts, very much as they would have been when trapping was carried out using Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust mink rafts. However, the use of an RMD reduces the time taken to keep traps running by some 98% compared to GWCT raft trapping, which relies on detecting mink by footprints on a clay pad before starting to trap. The electronics allow the traps to remain working 24/7, 365 days a year, as they only need checking when prompted or once every few months to ensure everything stays in good condition.

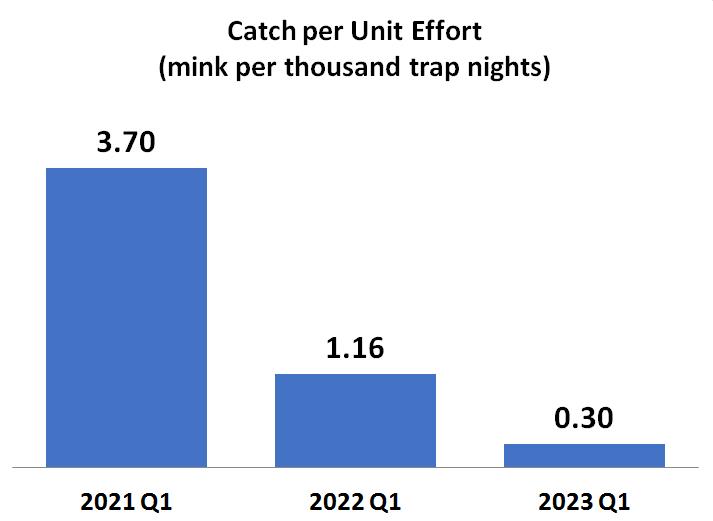

We now have nearly 700 smart traps active across the project area and this has reduced mink to very low levels. The best proxy we have for the rate of decline in the population is comparing the catch per unit of trapping effort over a similar period each year. If we look at this measure for Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire combined for the first quarter of each year, we get an average annual decline of 71.5%. This indicates that we might have only 0.6% of the original population remaining by the end of the 4th year. In the Core only 6 mink have been caught in the first 4 months of 2023, and importantly there is also no evidence that mink bred in the Core in 2022. If we really have reduced the population sufficiently to prevented breeding then eradication at landscape scale using trapping alone really is possible.

The sweet smell of success….

Getting to very low population levels in the Core so quickly took us rather by surprise but it was probably due to a combination of factors. First, the availability of RMDs and a sufficient density of smart rafts over the area. We believe that these have been made more effective, particularly in the mating season, by the addition of anal gland lure to the traps. The anal glands of all mink that are taken are palpated to extract the secretion, which is then put onto cigarette filters and placed in a hollow plastic golf ball attached to the top of the trap. The smell is anything but sweet; suffice it to say that those extracting the lure never caught Covid – no one would come near them!

We also use science to understand what is happening with the population. We take details of all mink caught, such as their sex and weight and they are aged by looking at the size of the pulp cavity of the canines coupled with counting the annual rings in a thin section of the tooth. All such data is recorded on a cloud database, along with the locations of all traps and all trap visits, which allows us to keep track of what is happening over the whole trapping area and model the population.

Ear Ear….

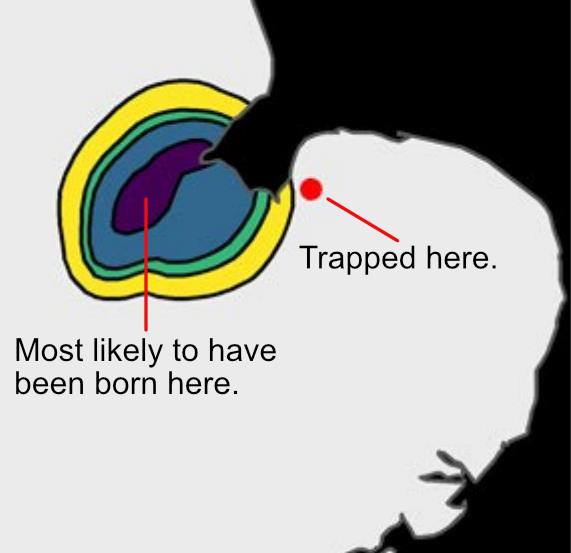

The science continues with genetic analysis, although it is just the tip of one ear that is taken from every mink, and this goes to Professor Bill Amos’s lab in Cambridge for the DNA to be extracted. Looking at that in detail, Bill can calculate who is related to who, can confirm the sex of the animal and even tell us where it was likely to have been born. This latter information is possible because he has now processed tissues from hundreds of mink from over a wide geographical area and is able to map the genotypes that are typical of each area. He can then help us answer questions like, ‘where on earth did that one come from!’. One such was a female caught rather unexpectedly on the River Babingley in North Norfolk on 1 April 2022. The DNA indicated that this animal was probably born in the western corner of the Wash, probably in the river Welland catchment, and in all probability moved round the Wash until she reached the mouth of the Great Ouse, then into the Babingley and finally into one of our traps.

Where next?

The success of the initial project has led to wider interest in using the best practice that we have been developing, and mink control projects are springing up all around the country from the Eden Rivers Trust in the Lake District, and in Northumberland in the north, in Lincolnshire and down to Kent and Sussex in the south. To better support this growing interest a charity, The Waterlife Recovery Trust (WRT) was formed in 2022. This would help make real the initial vision of WRE, to eventually eradicate mink from the whole of the country. Professor Tony Martin, who has been a driving force in what has been achieved so far, is the first Chair of the new charity. The Trust is currently applying for a significant Species Recovery Programme grant from Natural England, which if successful, would allow trapping to move out from Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire into adjoining counties. This would help cement the gains already made, push the boundary of control to the west, north and south and deliver intensive mink trapping over some 20% of England. You can follow the development of our ambition via the WRT website at https://www.waterliferecoverytrust.org.uk/, where you can also sign up for the quarterly Newsletter.

Simon Baker

Vice Chair, Waterlife Recovery Trust

Related Posts

If you enjoyed reading this, then please explore our other articles below: